How a Simple Tea Stall Explains Operating Leverage, Pricing Power, Cost Structure and Why Investors Keep Getting Cycles Wrong

Most investors believe they lose money because they misjudge growth. They think they were too optimistic about demand, too early on a turnaround, or too trusting of management projections. That explanation feels reasonable, even sophisticated. It also lets us believe that with better forecasts, sharper models, or more data, the outcome would have been different.

The uncomfortable reality is that many investing mistakes have nothing to do with growth at all. They come from misunderstanding cost structure. Long before strategy fails, before demand surprises, and before management narratives collapse, the way a business chooses to spend money quietly determines how it will behave under pressure. Once that behavior is forced, outcomes stop being flexible.

To understand this properly, it helps to forget stock markets for a moment and return to something simpler and more honest: a tea stall.

Two tea sellers, same product, radically different futures

Imagine two people selling tea on the same street. They use the same tea leaves, the same milk, and charge the same ₹10 per cup. From the customer’s perspective, the tea is interchangeable. From an investor’s perspective, however, these two businesses could not be more different.

The first seller runs a pushcart. He has no rent, no staff, and no long-term commitments. He buys milk daily and works alone. If demand falls tomorrow, he sells fewer cups and his costs automatically shrink with sales. His business is flexible by design.

The second seller runs a small café. He pays monthly rent, employs two staff members, and has purchased a tea machine on EMI. Even if not a single customer walks in tomorrow, his costs do not disappear. They sit there, waiting to be paid. His business is rigid by design.

At this point, it is natural to ask which business feels safer. Most readers instinctively side with the pushcart. It survives uncertainty better. It sleeps better at night. That instinct is correct, but only if survival is the goal. Wealth creation is a different game, and this is where operating leverage enters the picture.

Operating leverage is not a formula, it is a phase change

Operating leverage is often explained through ratios and equations, which makes it sound abstract and academic. In reality, it is painfully concrete. It simply describes how sensitive profits are to changes in sales.

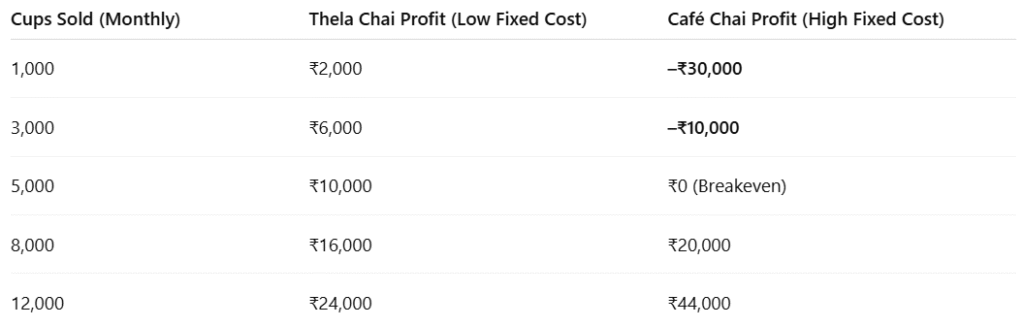

In the early days, the café suffers. When sales are low, fixed costs dominate the income statement and losses feel endless. The pushcart, meanwhile, muddles through with small but steady profits. This is why high fixed-cost businesses look fragile and poorly run during slow periods. Their numbers make them look broken.

But something important happens when demand rises beyond a certain point. The café’s rent, salaries, and machine costs do not increase with each extra cup sold. Once breakeven is crossed, each additional cup contributes disproportionately to profit. The pushcart continues to earn steadily, but the café’s profits suddenly accelerate. Nothing magical has happened. The cost structure has simply flipped from enemy to ally.

This is operating leverage. It is not good or bad in isolation. It magnifies whatever else the business already has. That is why the same structure that looks reckless in bad times can look brilliant in good times, and why investors often get the timing exactly wrong.

Fixed costs do not just affect profits, they force behaviour

One of the biggest mistakes investors make is treating fixed costs as static numbers rather than dynamic pressures. Fixed costs do not merely sit on the income statement; they shape how a business behaves when reality deviates from expectations.

A business with high fixed costs cannot afford idle capacity. When demand weakens, it does not have the luxury of patience. It must chase volume, even if that means cutting prices or accepting unattractive customers. This aggression is not a strategic choice. It is forced by the need to cover commitments that do not go away.

A business with low fixed costs behaves very differently. It can slow down. It can refuse bad business. It can wait for conditions to improve. That flexibility becomes a competitive advantage during downturns, even if it limits upside during booms.

This is why cost structure is destiny. Once you commit to it, your reactions to stress are largely pre-written.

Pricing power decides whether operating leverage works or kills

Operating leverage on its own is dangerous. What determines whether it creates wealth or destroys it is pricing power.

Return to the café. Suppose milk prices rise sharply. The café owner now faces a choice: absorb the higher cost and suffer margin compression, raise prices and risk losing customers, or shut down. If customers accept a higher tea price without materially reducing demand, the café survives the shock. If they do not, the same fixed costs that once promised scale now threaten survival.

Pricing power, stripped of jargon, is simply the ability to pass cost volatility to customers without losing volume in a meaningful way. It does not come from arrogance or market share alone. It comes from habit, trust, inconvenience, and psychology. When price is not the primary decision variable for the customer, pricing power exists.

This is why daily essentials often have more durable pricing power than luxury goods. A luxury purchase can be postponed. Toothpaste, tea, or basic food items usually cannot. Investors often overestimate visible, glamorous pricing power and underestimate quiet, habitual pricing power that compounds year after year.

Most people misunderstand brands, and overpay for the wrong ones

When asked why a large FMCG company can raise prices while a smaller competitor cannot, many people respond with a single word: brand. That answer is directionally correct but intellectually shallow.

A brand that creates pricing power does not merely trigger recall. It reduces decision-making. It tells the customer, “This is safe, familiar, and not worth rethinking today.” When that mental shortcut exists, small price increases do not lead to large behavioural changes. That is the real asset.

Brands that rely on novelty, aspiration, or occasional indulgence behave very differently across cycles. Their pricing power often disappears precisely when operating leverage becomes dangerous. Investors who fail to distinguish between these two types of brands pay for it during downturns.

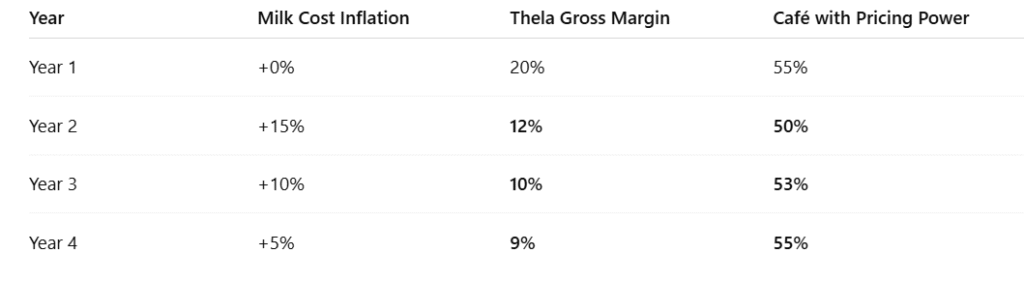

The hidden cycle that traps investors again and again

Markets talk about cycles in terms of demand, but the more important cycle runs inside cost structures. It begins quietly, often when things look healthiest.

During stable periods, profits rise and confidence builds. Companies expand capacity, add fixed costs, and often take on debt because everything looks manageable at peak margins. At this stage, valuations often appear reasonable on trailing earnings, which attracts capital rather than caution.

When conditions change through cost inflation, competition, or slowing demand, rigid cost structures reveal themselves. Margins crack faster than expected. Businesses discount to protect volume. Cash flows weaken. This is when panic sets in and narratives turn negative.

Eventually, losses peak. Capacity is cut. Behaviour adjusts. Then something subtle but important happens. Losses begin to shrink, margins stabilise, and pricing discipline quietly returns. Revenue may still be falling, headlines may still be pessimistic, but internally the damage has stopped worsening. This is the beginning of recovery, even though it feels unsafe.

Markets tend to re-rate businesses at this point, well before earnings look attractive again. Investors who wait for visible growth often arrive after operating leverage has already done its work.

The insight most investors miss about recovery

Recovery does not start with growth. It starts with margins and behaviour.

When you see a business with declining revenue but shrinking losses and improving margins, the instinctive reaction is often to wait for confirmation. But from a cost-structure perspective, this is frequently the moment when risk has already peaked. Fixed costs are no longer accelerating damage. Pricing power, if it exists, is reasserting itself. Operating leverage is quietly turning positive.

Markets reward change in trajectory, not comfort. That is why the best opportunities often feel irresponsible at the time and obvious in hindsight.

How to actually use this as an investor

When analyzing any business, especially one emerging from stress, it is worth asking a few uncomfortable questions. Who is forced to blink first when conditions worsen—the business or the customer? Do fixed costs force aggressive behavior, or does the company retain flexibility? Have margins recovered after past cost shocks, or do they permanently degrade? Does revenue grow quietly even when volumes stagnate? Does return on capital remain high without constant reinvestment?

These questions do not produce neat scores or precise targets. They do something more valuable. They force you to confront how the business will behave when things do not go according to plan.

Why boring businesses stay expensive

Businesses with habitual demand, real pricing power, and cost structures that work after breakeven rarely look cheap. They do not promise excitement. They offer reliability. Inflation does not scare them; it often helps them. Cycles do not destroy them; they expose weaker competitors.

Markets may resist paying up for this reliability in the short term, but over long periods, they almost always do.

A final question worth sitting with

The next time you encounter a company reporting falling revenue, shrinking losses, improving margins, and deeply pessimistic sentiment, ask yourself whether you are witnessing the middle of a decline or the beginning of a hidden recovery. The answer to that question will matter far more than any single valuation multiple.

Closing thought

Strategy can change. Management can change. Narratives change every quarter.

Cost structure does not. And it never forgives misunderstanding.

Once you start seeing businesses through this lens, investing becomes less about prediction and more about recognition. You stop chasing stories and start respecting inevitabilities. That shift is quiet, uncomfortable, and deeply powerful, and it is where serious investing actually begins.

If you liked this blog, you might enjoy my previous ones as well:

👉 Why Cheap Stocks Trap You — The Psychology Behind It

👉Why Nifty Is at All Time Highs but Your Portfolio Is in the Basement

👉AI Won’t Crash Like 2000. It Might Correct Like 2008 — When Reality Finally Shows Up.

👉Strong USD Is Not a Modi Issue or a Congress Issue — It’s Global

👉 Why We Feel Smarter After a Stock Falls: The Psychology of Market Regret

👉 Why Comparing Your Portfolio to Others Destroys Your Returns

👉Is Your Stock a Hidden Pump-and-Dump?

Harsh is the creator of Dalal Street Lens, where he writes about investing, market behaviour, and financial psychology in a clear and easy way. He shares insights based on personal experiences, observations, and years of learning how real investors think and make decisions.

Harsh focuses on simplifying complex financial ideas so readers can build better judgment without hype or predictions.

You can reach him at imharshbhojwani@gmail.com

More from Dalal Street Lens

Most Investors Misread Accent Microcell. This Is the Real Business.

Most Investors Misread Accent Microcell. This Is the Real Business. Costco Business Model Explained: Why Costco Feels Different the Moment You Walk In

Costco Business Model Explained: Why Costco Feels Different the Moment You Walk In McDonald’s Business Model Explained: Why It’s Not Really About Burgers

McDonald’s Business Model Explained: Why It’s Not Really About Burgers Jesse Livermore Lessons

Jesse Livermore Lessons Karnataka Bank Earnings Call Analysis – November 2025

Karnataka Bank Earnings Call Analysis – November 2025 How Nassim Taleb’s Trading Philosophy Changed the Way I Look at Confidence in Markets

How Nassim Taleb’s Trading Philosophy Changed the Way I Look at Confidence in Markets Retail Investors vs Institutional Investors

Retail Investors vs Institutional Investors Second Order Thinking in Investing: Four Decisions I Had to Learn the Hard Way

Second Order Thinking in Investing: Four Decisions I Had to Learn the Hard Way The Attention Economy Trade: Who Really Makes Money When Global Stars Visit India

The Attention Economy Trade: Who Really Makes Money When Global Stars Visit India India’s Data Centre Supercycle: The Simplest Explanation of Colo, Cloud and AI Infrastructure

India’s Data Centre Supercycle: The Simplest Explanation of Colo, Cloud and AI Infrastructure

Ur writing skill is too Good

Keep it up