It took me longer than it should have to admit this, but most of my investing mistakes didn’t come from ignorance. They came from moments when things finally felt clear. When the numbers made sense. When the story settled. When acting felt… responsible.

Looking back, those were usually the worst moments to act.

I used to think second order thinking in investing was some clever mental trick, a way to outsmart the crowd. Over time, I realized that’s not what it is at all. In practice, it’s a very narrow skill. It appears only at specific moments. Miss those moments, and no amount of intelligence elsewhere helps.

This isn’t an article about the concept.

It’s about those moments.

Buying After Good News

I’ve bought more stocks after good news than I care to remember. Not impulsively. Not emotionally. Calmly. With reasons.

The pattern was almost always the same. Weeks before the results, the stock would stop reacting negatively to small disappointments. Price would firm up. Analysts would sound a little more confident. Nothing dramatic, just a subtle shift in tone. By the time the quarter actually came out strong, it felt less like news and more like confirmation.

That feeling is dangerous.

When you buy after good news, you’re rarely responding to new information. You’re responding to information that has already been partially absorbed. The market has quietly adjusted its view of the future, and that adjustment shows up in the price you’re willing to pay and the margin of safety you’re willing to give up.

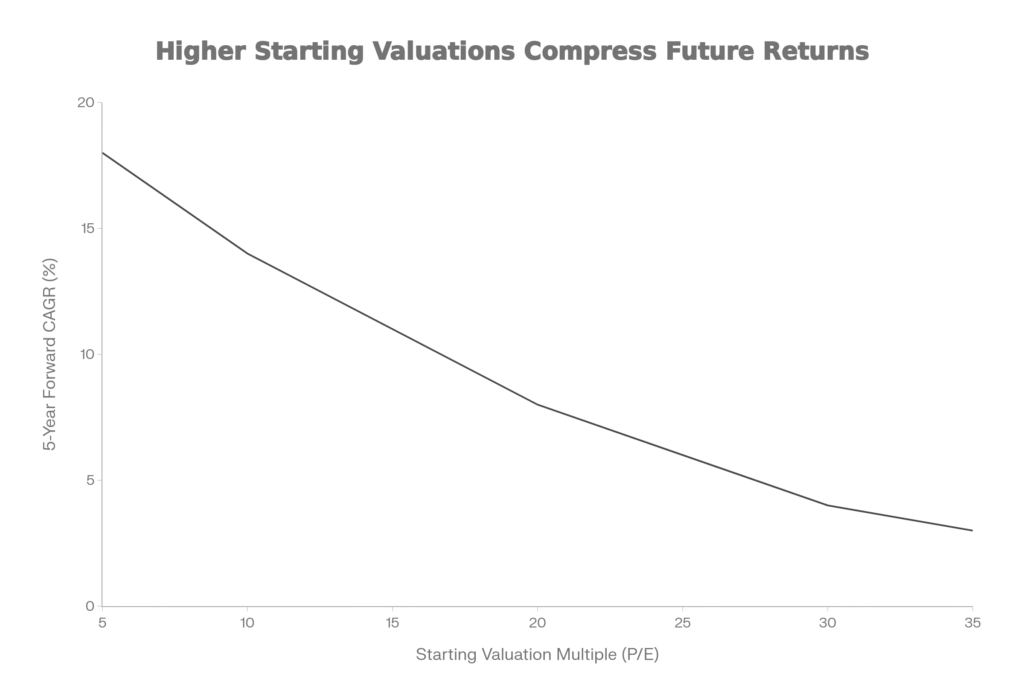

This is where the word expectations often gets used loosely, so let me be precise. Expectations aren’t a mood or a narrative. They are embedded in valuation. They live in the multiple you accept today and in how much growth the business must now deliver just to avoid disappointing you tomorrow.

This is why clarity is expensive. As valuations rise ahead of certainty, future returns compress, not because growth disappears, but because perfection has already been prepaid.

Second order thinking here doesn’t say “avoid good companies.” It asks whether you are buying improvement or simply buying recognition. I didn’t understand that distinction early enough. You might be noticing it now.

Selling After Bad News

There is a particular kind of relief that comes from selling after bad news. I know it well.

The quarter disappoints. The stock falls hard. Everyone suddenly has an opinion. Selling doesn’t feel like panic, it feels like discipline. Like protecting capital. Like being sensible.

What took me time to understand is that price declines after bad news are rarely clean signals. They usually mix two forces that look identical on a chart: new information and forced behaviour.

Funds hit mandate limits. Leverage gets reduced. Risk committees step in. Time runs out for someone else. The selling accelerates, not necessarily because the business is broken, but because patience has become unaffordable.

The difficult question, in the moment, is not whether the news is bad. It’s whether the business’s long-term ability to survive and generate cash has fundamentally changed, or whether the market has temporarily lost its ability to wait.

I’ve sold stocks to feel better. The relief was immediate. The regret arrived slowly.

Second order thinking here isn’t about being brave or contrarian. It’s about distinguishing discomfort from impairment, a distinction that only becomes obvious after the selling has already begun.

Holding a Winner

This decision still tests me.

A stock runs up. The position grows. Valuation starts to look uncomfortable. Selling feels prudent, even mature. After all, nobody ever went broke taking profits.

But price alone doesn’t tell you whether risk has increased. What matters is what the price now assumes about the future.

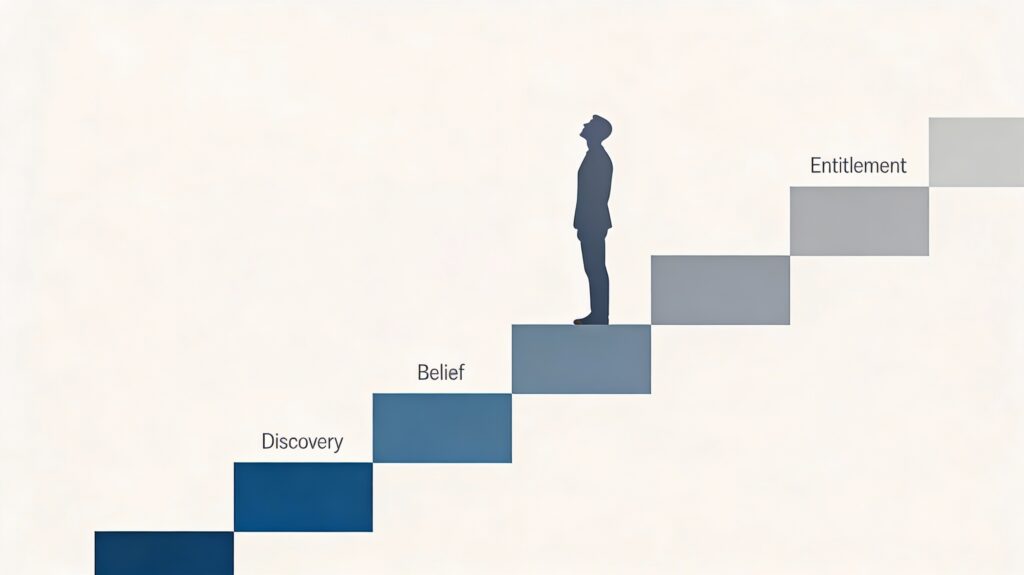

Sometimes a stock has risen because the market is still discovering it. Sometimes it has risen because belief has hardened into entitlement. Those two situations feel identical emotionally and look very different only in hindsight.

I’ve exited winners too early because the gains felt excessive. I’ve also stayed too long because the story felt unbreakable. In both cases, the mistake was the same: anchoring on price instead of asking what the price now demanded from reality.

Second order thinking here isn’t clever. It’s uncomfortable. It asks whether the future needs to be exceptional just to justify staying put. When that’s the case, compounding quietly becomes fragile.

Most investors don’t lose money here. They lose time. And time is harder to recover.

Doing Nothing

This is the decision I violated most often, and noticed last.

There are long stretches in markets when nothing looks obviously cheap or broken. Narratives are loud. Opportunities feel scarce. Cash starts to feel like a mistake.

I used to fill those stretches with activity. Not recklessly, just enough to feel engaged. Each trade made sense on its own. Together, they quietly eroded returns.

Doing nothing feels passive. It isn’t. It’s a decision to wait for asymmetry instead of clarity. It’s an acknowledgment that when prices already reflect confidence or fear, action often carries more downside than upside.

I still feel the urge to act in these phases. I just recognise it sooner now.

Where Second Order Thinking Breaks

Second order thinking isn’t a shield. It has its own failure modes.

You can overthink. You can wait forever. You can mistake complexity for depth. I’ve done all three.

The point isn’t to think endlessly. It’s to recognize the few moments where thinking one level deeper actually changes the decision, and to act decisively when it does.

Why This Matters

Second order thinking didn’t make me smarter.

It made me slower, selectively.

It taught me to hesitate when action feels justified. To question relief. To notice when clarity arrives suspiciously late.

If this piece works, it won’t give you answers. It will interrupt you, briefly, right before you do something that feels obvious.

That interruption is small. Quiet. Easy to ignore.

It’s also where most long-term investing damage quietly begins.

Harsh is the creator of Dalal Street Lens, where he writes about investing, market behaviour, and financial psychology in a clear and easy way. He shares insights based on personal experiences, observations, and years of learning how real investors think and make decisions.

Harsh focuses on simplifying complex financial ideas so readers can build better judgment without hype or predictions.

You can reach him at imharshbhojwani@gmail.com

More from Dalal Street Lens

Most Investors Misread Accent Microcell. This Is the Real Business.

Most Investors Misread Accent Microcell. This Is the Real Business. Costco Business Model Explained: Why Costco Feels Different the Moment You Walk In

Costco Business Model Explained: Why Costco Feels Different the Moment You Walk In McDonald’s Business Model Explained: Why It’s Not Really About Burgers

McDonald’s Business Model Explained: Why It’s Not Really About Burgers Jesse Livermore Lessons

Jesse Livermore Lessons Karnataka Bank Earnings Call Analysis – November 2025

Karnataka Bank Earnings Call Analysis – November 2025 How Nassim Taleb’s Trading Philosophy Changed the Way I Look at Confidence in Markets

How Nassim Taleb’s Trading Philosophy Changed the Way I Look at Confidence in Markets Retail Investors vs Institutional Investors

Retail Investors vs Institutional Investors Cost Structure Is Destiny

Cost Structure Is Destiny The Attention Economy Trade: Who Really Makes Money When Global Stars Visit India

The Attention Economy Trade: Who Really Makes Money When Global Stars Visit India India’s Data Centre Supercycle: The Simplest Explanation of Colo, Cloud and AI Infrastructure

India’s Data Centre Supercycle: The Simplest Explanation of Colo, Cloud and AI Infrastructure